Years ago, I read George MacDonald’s 1879 novel, The Baronet's Song (also titled, Wee Sir Gibbie). It’s about a young, mute, Scottish boy raised, then orphaned, by an abusive, alcoholic father. Gibbie finally ends up being adopted by an elderly couple and the old woman, Janet, becomes a mentor to the pure-in-heart boy. Seeing the face of Jesus in him, she teaches him everything she has ever loved about Jesus (which was very different than the hellfire and brimstone being preached in the churches!). Writes MacDonald, "So teaching him only that which she loved, not that which she had been taught, Janet read to Gibbie of Jesus and talked to him of Jesus, until at length his whole soul was filled with the Man, of His doings, of His words, of His thoughts, of His life. Almost before he knew, he was trying to fashion his life after the Master. Janet had no inclination to trouble her own head, or Gibbie's heart, with what men call the plan of salvation. It was enough to her to find that he followed her Master." Prayers of salvation and baptism (so he would not go to hell) were of no concern to Janet. She simply shared with him the life of the One who taught her how to walk in the way that leads to Life. I finished that novel and began reading more novels of George MacDonald's, The Curate's Awakening, The Musician's Quest, The Lady's Confession, The Poet's Homecoming, The Fisherman's Lady, The Marquis' Secret and more...amazed at the way his characters experienced and trusted in (& their lives reflected) an unrelentingly kind and tender God. Each time I would say to myself, "I want to trust God and speak of Jesus in that way." And slowly like Janet had done for Gibbie, George MacDonald did for me. Sometimes what we have been taught or picked up on in regard to salvation does not lead to the freedom or life of which Jesus spoke. It does not cause the heart to long to know and trust that God more. Says Meister Eckhart in Daniel Ladinsky's Love Poems from God, "How long will grown men and women in this world When you think of God, does the image that comes to your mind make you sad or fearful?

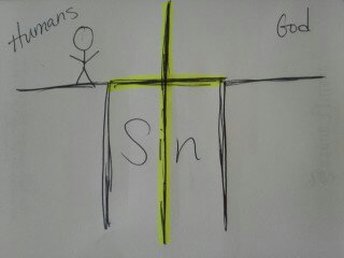

Or is it an image your heart dearly loves? If you prayed the prayer of salvation or were baptized, what was that like for you? What motivated you to do so? A welcome into and communal acknowledgement of following Jesus on the path of Life? Or wanting to be saved from hell and eternal punishment? If both rituals initiated you into living a life of Love, I am so very glad for you (my baptism was very meaningful to me). But if either were fear-motivated, perhaps it is time to recognize any grasp it still has on you, especially if fear-based theology continues hissing in your ear. Stories around salvation and baptism reverberate throughout one's life, for better or for worse. And fear-based theology can offer nothing (no matter how convincing!) but fear-based lenses to view one's self and the world. Maybe it's time for a trip to the library to spend time with George MacDonald's characters. Maybe it's time to come to Spiritual Direction and experience the God of Wee Sir Gibbie. Maybe it's time to pick up your crayon and draw a different image in your coloring book.  It’s what we tend to do. Most Christians have an entire theology built on it. Someone/something must pay for others’ sins. Sin is burdensome, whether it’s our own or the world’s! It can’t be ignored (at least not forever). If ignored, it will still be felt in our physical bodies or relationships. The more it's ignored, the greater the natural consequences from the unacknowledged harm to ourselves, others, and/or the created world. So it’s no surprise that people have been trying to figure out what to do with the problem of sin for millennia. We are a ritualistic people. In Leviticus 16 found in the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament), it was a ritual with an actual goat (hence the term, “scapegoat”) that helped relieve the communal burden. The impurities of the community were transferred to the goat through the “laying on of hands.” Then the goat was beaten and released into the wilderness to take away the sins of the Israelite people. The despised goat symbolically took on their sins and carried them away from the community. In the New Testament, the writer of the book of John records John the Baptist pointing out the role of the scapegoat being taken on by Jesus when he proclaims, "Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world." It’s human nature to look for a scapegoat, especially when we do not want to or do not know how to deal with sin. Watching small children (as well as our current politicians) will make that apparent quite quickly. Their mantra: "Make it someone else’s fault!" It’s especially natural if we’ve grown up with a theology that espouses it. It’s too easy to believe that when Jesus takes away my sin, I no longer have to deal with it or the consequences of it (someone else has paid the ultimate price after all). The danger of this theology is that it can shift the focus to worshipping Jesus because of his offering of “fire insurance” for the life to come rather than following Jesus as a disciple in this one. If we happen to be Christians who believe Jesus paid the price as the ultimate scapegoat (which made him the last needed scapegoat), why do we still continue to scapegoat others?—Democrats, Republicans, Black people, Indigenous people, White people, LGBTQ people, police officers, protestors, teachers, certain members of our families… If Jesus is the ultimate scapegoat, that means we are now freed from scapegoating others! We are a ritualistic people in need of a new ritual. If we don’t have anyone to blame or transfer our sin to, what happens next?  My first sketch of "the bridge" in 15 years! My first sketch of "the bridge" in 15 years! During my first semester of college I was taught the "4 Spiritual Laws" at a nearby church and campus ministry. I couldn't believe how much sense it made! Why hadn't I seen this before?! It was so logical. Being a Jesus-follower AND rule-follower, here were 4 spiritual rules about salvation that someone had culled from the Bible that I could not only believe in but easily explain to others. And I did for years, until... My internal dissonance grew louder. This was experienced as confusion, anger, and not wanting to go to church or sing which led to guilt for feeling that way at all. Of course being a rule-follower and "good girl," I forced myself to go (although I no longer sang or shared this "Good News" with anyone). At the time I had no answer as to "why," but I started noticing something else. My body kept trying to tell my mind something. Gone was the excitement my rational mind had that first year of college and the following eight years. Whenever singing, explaining or hearing this theology, I felt a growing tension in my chest, pit in my stomach, and increase in headaches. Unbeknownst to me, the "Good News" wasn't being recognized as good by other parts of me (this is important since we're to love God with not only mind, but heart and body as well). It took me a long time to discern what was going on for there were several issues related to church and Christianity that God was intent on bringing to the surface to heal. Parts of me are still in this healing process. Knowing my kids will be presented with this same theology at some point, a couple of weeks ago, I decided to get my young daughter's response to the 4 Spiritual Laws and the bridge drawing that goes along with it (seen above). I also tend to ask my kids their point-of-view when it comes to difficult theological concepts because they don't have the theological/church baggage I do and they know they have permission to offer an honest opinion. After school one day I said to her, "Hey, I want to show you something that I was taught and get your opinion on it." After looking and listening to me talk about sinful humanity, a perfect God, sin separating us from this perfect God, and the cross as the bridge, here's what she said: "That's a clever drawing! BUT, here's the problem (she pointed to the sides), the starting place is all wrong." I asked her to say more. "Well, that's only the starting place through a human's eyes, it's not the starting place through God's. It's like when I'm all anxious, I think no one understands me and I'm completely alone, but the reality is, I'm not. Same with God." Wow. And there you have it folks. That's why Jesus said to become like a child if you want to enter (or even recognize) the Kingdom! Leave it to a child to cut through all the theological, rational laws and offer a simple but profound apologetic. God is with us...period. And as my 10-year-old daughter went onto tell me, "Not seeing this is the beginning of 'missing the mark.'" It's taken me years to get back to this starting point! Her intuitive theology resonates with that of King David in Psalm 139 (who needed no bridge for he knew God to be everywhere he was and went, inescapable within and without!). Whether we see it or not, God, the Ever-Present Love, is with us. Jesus the Christ and "the old rugged cross" is this message in vivid color! May God give us the eyes of a child.

The following poem was spontaneously written in 2012. God knew I was exhausted by two young children and years of wrestling with atonement theology (unable to put into words my growing inner dissonance with the popular view of the cross). Not being a poet, I was shocked when out-of-the-blue, poetry began flowing. I literally had a pen in one hand barely able to keep up with the free-flow of words and a spoon in the other stirring the kids' macaroni & cheese! A couple of notes about this poem: Philosopher Girard refers to Rene Girard who said the scapegoat mechanism is the origin of sacrifice in all cultures and the Bible both reveals and denounces it. The last word of the poem brings together both John 14:6 and Psalm 119:105. They speak of You paying the price for our sins, of this Ultimate Sacrifice As if Your visible vulnerability were not enough Our Creator, the Creator of all, coming to this land a crying baby boy and leaving a bleeding and broken man What more sacrifice do we want? What is left to be paid? In pain we look for a purpose, the greater the reason the more our pain allayed You say You delight not in burnt offerings, and You neither require nor drink the blood of goats But how can we trust such words to be true? Sacrifice and religion, dare we separate the two, even if it be a marriage of convenience and not of love? We give such reasons so scared for them to fail, but what if we sacrifice reason and find our scapegoating revealed? I tell you philosopher Girard was never so happy as when he put to Western words such ancient discovery! What revelation! To step outside sacrifice, to see her for who she is, tis like naming a covenant new You indeed paid a price Man of Sorrows, and told us to follow You Find life and eternal joy by being well-acquainted with grief You died because of our sins in the manner of a thief It was not Your blood that was needed in order to make us right, but it was Your blood that showed You to be the Way, the Truth, and the Light.  Image found at www.rogerebert.com/reviews/gran-torino-2008 Image found at www.rogerebert.com/reviews/gran-torino-2008 Good Friday is coming in a few weeks and with it, some theology I simply cannot stand anymore. It's found in many worship songs like Jesus Paid it All, In Christ Alone, One Thing Remains (Your Love Never Fails) and more. It's called substitutionary atonement or penal substitution in theological language. And it's heard so often, you might even think it's the only show in town when it comes to explanations and understandings of the cross. Richard Rohr, writes in Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi, “For the sake of simplicity and brevity here, let me say that the common Christian reading of the Bible is that Jesus 'died for our sins'— either to pay a debt to the devil (common in the first millennium) or to pay a debt to God the Father (proposed by Anselm of Canterbury [1033–1109] and has often been called 'the most unfortunately successful piece of theology ever written')..." I could not agree more. No matter how sweet sounding the music, the image of God portrayed by such lyrics is a petty, powerless and/or blood-thirsty tyrant requiring some kind of payment or transaction before those He's created can be forgiven, loved, and rescued from eternal damnation. There are lots of problems with this theory. One major problem is that if we read the Hebrew Scriptures, like the Psalms and Prophets, we discover a long-suffering God who was forgiving and willing to forgive long before the cross occurred. Rather than a belief that Jesus' death on the cross was necessary to change God's mind about us, we can see how Jesus' life and death invited us to change our minds about God. Jesus was simply following in his Father's footsteps of relentless, sacrificial love. I have a problem with lyrics and theology that proclaim the opposite. Given this theology is taught through song and sermon in many churches (I taught it years ago as a youth pastor!), we're not apt to actually stop and think through it ourselves. It took me a while to admit that something seemed "off." There would be songs that seemed fine up until the "wrath" or "debt paid" lyrics showed up affecting the whole song. As I questioned this dominant cultural voice in American Christianity, I realized there were others experiencing the same internal dissonance. I also discovered there were other views about the crucifixion (always have been) besides substitutionary atonement. And that one no longer represents my viewpoint... The movie, Gran Torino, on the other hand does. Spoiler alert, if you haven't seen it and want to, you may want to stop reading, go watch it and come back later. And be aware, there's violence (although let's be honest, there has to be if drawing any kind of connection between it and Good Friday). Back to the movie, I did not see it coming, the ending of Gran Torino. In fact, I imagine I got a taste of being stunned the way the disciples might have been stunned on that Good Friday long ago...they simply never saw it coming. Yet the Gospels tell us Jesus did (and so did Clint Eastwood). If you saw the movie but cannot remember the ending, go check out a Youtube clip of the end. The final scene is so rich in symbolism, I'm not even going to get into all of it (plus it would take away from your own disturbances and observations). All I know is that Gran Torino gave a pretty good glimpse of my view of Jesus' death on the cross in less than 5 minutes. A quick overview of the movie...gruff Walt Kowalski (played by Clint Eastwood) is a recently widowed Korean vet. He's fairly estranged from his own family when he gets drawn into the drama of his Hmong neighbors. Young Thao tries to steal Kowalski's Gran Torino after being pressured by his cousin to join the neighborhood gang. You know that Eastwood is not going to let that happen! This event leads to Kowalski developing a relationship with the family and getting an inside look at the cycle of violence and poverty experienced by the Asian community in his neighborhood. He sees how his well-intentioned advice to Thao to get a decent job and stay away from the gangs simply doesn't work, no matter how hard Thao tries, he and his sister cannot escape the brutality and injustice. It requires something more to liberate Thao and his sister. And that's where we start seeing Kowalski's single-minded intensity and there's no mistaking he is planning something. What he's planning, we have no idea. Although we know something is about to take place when one night he shows up at the house where the gang members hang out and begins to yell in order to provoke them. One by one they come out with guns drawn. We're expecting "an eye for an eye" moment thinking Eastwood will whip out a gun and give them the justice they deserve by picking them off all in a row. What we're not expecting from the foul-mouthed Kowalski is "Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends." (John 15:13) And yet he does. And on purpose. His stunning and creative act of solidarity and sacrifice releases Thao and his sister from the cycle of violence. They were "saved" by his blood. In a perfect world, the prison system would reform the perpetrators and they'd be "saved by his blood," too. It's not a perfect world and Walt doesn't rise again in three days, so there's only so far the comparisons can go but I think it's worth noting the image of Christ found in Walt's sacrifice. First, let's admit that Walt himself could be a stumbling block for some. In which case, I ask us to ponder what one who "walks in the way that leads to Life" really looks like. Is it being a nice, moral citizen who tries to avoid or point out sin (but can have a habit of ignoring the cycles of violence and systemic injustice in his own "neighborhood")? Or might one resemble Walt, a crass, politically incorrect "sinner" who not only notices the violence and injustice, but steps into a Christ-like path which will set his neighborhood free? Setting his face like flint, he walks right onto that sidewalk for an act of love which will rescue his neighbors from being held captive by a cycle of violence they are powerless against. Sound familiar? Jesus knew his message would provoke the authorities. He knew that such ire would inevitably turn him into a scapegoat (a person or people group on whom we unfairly pour out our wrath, making them "pay"). He knew it is human nature to look for a scapegoat. So much so, it becomes a religious necessity for nearly every culture (some even beating literal goats to death as the name suggests)! One can see how Jesus' bold message about what to do with friends and enemies does not fit, but in fact destroys both the necessity for and violent cycle of sinful and superstitious scapegoating. Bigger isn't better in Jesus' view (even when it comes to God). Being the stronger bully or in the bully's gang never leads to the kind of life Jesus invites, it only adds fuel to the cycle of vengeance. However, many Christians have no problem with this because the image of God passionately sung about is a fickle, vengeful one (and remember, we become like the God we worship). Plus if we agree that Jesus paid it all, we're safely on the winning side. However, in the cycle of violence, there is no winning side. In a stunning reversal of what we would expect from a winning "savior," Jesus chooses solidarity with the suffering of the scapegoat and dies. Jesus knew the pull of scapegoating loomed large. After his resurrection, knowing some of his disciples had a propensity for zealous anger (once they knew they were safely on the "winning team"), he headed off any plans to go after the ones who had killed him. The Gospel of John tells us Jesus meets his disciples in the room they were hiding in, breathes on them, tells them to receive the Holy Spirit then talks to them about forgiveness (20:21), a topic he talked to them about at the Last Supper and even voiced from the cross. It seems the disciples had a choice (and so do we). Be chained to the cycle of violence or have hearts and minds freed up to carry out the mission Jesus began. What is that mission?--a completely different way of being in the world (which includes the religious one!). It's the subversive, dangerous and life-giving way of loving God and our neighbors (whether they be Hmong, Muslim, Mexican, Irish, disabled, poor, or LGBT+) as we love ourselves (which includes parts of ourselves we like and parts we'd like to treat as scapegoats). It's that kind of love that frees. It's that kind of love that Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., the young Palestinian girl Malala Yousafzai, and Walt Kowolski knew would cost them something, perhaps even their lives. If someone wants to write a song about that, I'll gladly sing it. |

AuthorKasey is a scarf, ball and club juggling spiritual director just outside of Nashville, TN. Play helps her Type-A, Enneagram 1 personality relax, creating space for poetry and other words to emerge. She also likes playing with theological ideas like perichoresis, and all the ways we're invited into this Triune dance. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

By clicking “Sign up for E-News” I consent to the collection and secure storage of this data as described in the Privacy Policy. The information provided on this form will be used to provide me with updates and marketing. I understand that I may modify or delete my data at any time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed